News

Na Te Tau-a-Nuku-a-Nuku

Posted 25 05 2020

in News

Ko Amelia Blundell (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu, Ngāti Pākehā) i tuhi

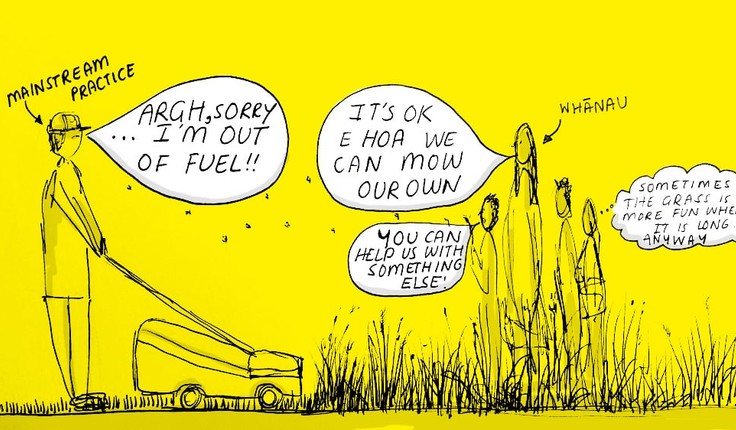

What happens if we can't mow the lawns?

The grass can grow.

Some preliminary findings and conclusions from my Master’s thesis research on decolonising mainstream placemaking practice in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

In a piece I wrote earlier this year I asked you all, as Landscape Architects, the same question I asked myself at the outset of the research; ‘koe wai hoki ahau?’ Who am I, who are we in the cultural landscapes of whānau, hapū and iwi? What does our mahi look like when we recognise and acknowledge the fundamental rights Māori have to determine their own lives and places. For me, these questions meant understanding (and often learning) our shared history, acknowledging my own bias, relinquishing control, coming out from behind the rules and learning how best to whakamana tāngata (value people) without appropriating. As I write this I cannot help but think of our current circumstances in isolation. Although this time may feel constrained by things we can no longer do and crowded by concerns of what we are going to do in the unforeseeable future, this time has also provided some of us with an opportunity to prioritise our whānau, communities and places- he waka eke noa, we’re all in this together.

The cartoon image tells a story of what it can feel like to engage with professional practice and to try and contribute to the formal decisions that get made about our places. What I learnt from our research is that you can have all the right people, with all the best intentions and ideas about a place, but if the communication is ineffective, we will continue to talk past one another and be stuck in what feels like an aroha triangle (Image 2). If there is to be true partnership, the one envisaged by Te Tiriti, manawhenua will no longer be collaborators or resistors in someone else's plan and this fragmented communication triangle will no longer exist. However, what the initial research indicates is that before partnership, comes restoration, and for this we need empathetic and effective communication. So how do we go about turning this triangle (communities/whānau, professionals, rules) into meaningful partnership? The following preliminary findings from the research could be read as an invitation for this kind of transformation. They are that we need to:

1. prioritise meaningful partnership with manawhenua. Approach manawhenua in reciprocity and ask what mainstream practice can do to be a better treaty partner (not just for the next project but in the long term). Be committed to listening and be in a position to transform accordingly.

2. avoid the instinct to define all things kaupapa Māori. Create systems, rules and be practitioners that can work with ambiguity and agile with your responses in order to learn from mistakes quickly.

3. systemically relinquish control over placemaking and whakamana other experts such as taitamariki (youth) and whānau. Turn design monologues into dialogues with others and recognise that good practice allows communities to be active agents in changing and shaping the process as well as the place.

4. observe, support and empower contemporary Māori place-makers and place-keepers. Ask networks such as Te Tau-a-Nuku, Ngā Aho and Papa Pounamu to collaborate in reimagining critical components of practice such as education and registration. Make room for difference and value contributions from manawhenua, kaimahi Māori, kaumatua, taitamariki and whānau.

5. promote and support new models of engagement (see for example AKAU’s model https://akau.co.nz/foundation). Put substantial time, resources and thought into transforming mainstream participation and engagement processes to work better with people instead of for people. Explore these processes outside of the constraints of a particular project to build trust with communities.

6. recognise acknowledging bias as a form of ‘good practice’. Reward collective process in the same ways practice currently rewards individual originality. Promote and celebrate design that responds to local communities and their environment.

7. prioritise and build cultural competency. Create resources and courses that educate practitioners on our shared history and its implications for their mahi. Show practitioners that te ao Māori need not be a box they must tick but an essential exercise in expanding their minds. Make knowing the karakia and waiata as ‘normal’ as discussing the design brief.

8. promote partnerships and relationships across sectors such as planning and architecture to avoid working in silos. Encourage local procurement that builds upon assets that already exist within communities.

If we hope to make good, and uniquely Aotearoa New Zealand places, then the restoration of the partnership envisioned in Te Tiriti must be recognised in any placemaking profession and activity of design. A central kaupapa to the research was grassroots placemaking, highlighting the power and agency of our communities in determining their places. What became clear to me was that often practice (unintentionally) acts as the lawn mower, maintaining standards but subsequently cutting away at new growth of our intrinsic and resilient communities, who each have enormous amounts of knowledge to contribute their places. There is a lot more to this profession than keeping on top of everything and there is much more to us than the work we do as landscape architects. Perhaps for our people and places, the best thing to do right now is to let, or maybe even help, them grow in whatever ways they need even if it feels outside our job description. The case study of the research, our friends at ĀKAU in Kaikohe, continue to pave the way for working and staying connected with whānau and communities despite being in isolation! Make sure to check out their design kete on their website and get going on creating a flag with your bubble.

Noho ora mai, stay well.

Mauri ora

This article shares the preliminary findings and conclusions from a master's thesis in architectural theory. I would like to acknowledge and thank all the people who contributed their time, kōrero and whakaaro to this research- ‘e hara taku toa i te toa takitahi, he toa takitini’. Additionally, I would like to acknowledge that this project (ID: 17-VUW-018) was funded by a Marsden Fund granted to Dr R.F. Kiddle, PI, Victoria University of Wellington, titled ‘Making Aotearoa Places: The Politics and Practice of Urban Māori Place-making’.

Amelia is a student and member of Te Tau-a-Nuku (The Māori Landscape Architects Collective) which is a part of Nga Aho; the Collective of Māori Design Professionals.

Share

12 Feb

NZILA lodges submission on Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill

There’s still time to have your say

Tuia Pito Ora New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects has lodged its formal submission on the Planning Bill and Natural …

09 Feb

Weekly international landscape, climate and urban design update

Monday 9 February

This is your weekly international snapshot of what’s happening across landscape architecture, climate adaptation and urban design. Drawing on credible …

02 Feb

RMA Reform submission update

Call for feedback and images

Submission framework The Environmental Legislation Working Group thanks all members who made the effort to join us at the national …

Events calendar

Full 2026 calendar