News

Papakainga Housing - a Taupo Case Study from Kara Scott

Posted 01 10 2018

in News

Na Te-Tau-a-Nuku

Papakāinga. It’s a traditional form of whānau-based communal living on ancestral Māori land that I strongly believe in; in terms of whānau support and well-being. I can’t help but feel passionate about it. So, when a papakāinga project in the Taupō District came up for a Tūrangi-based whānau, I jumped at the opportunity to be part of the project team.

Papakāinga, as I learned from a recent workshop held by Te Puni Kōkiri, can take lots of different forms. Traditionally it is located on ancestral Māori land, includes a cluster of houses that share infrastructure and resources, such as roading, services, gardens, utilities, and may include a shared wharenui. More modern papakāinga may be in the form of apartment living, or one large whare that sleeps dozens. Te Puni Kōkiri has really good resources and examples of different types of papakāinga, and there are businesses dedicated to facilitating the process for whanau.

Ancestral Māori land is often located in more remote parts of the countryside – it tends to be rural land. This rural land can take many forms; scrub or regenerating native bush, farmland, forestry, or even reclaimed former conservation land.

District plans, which set the rules and policy direction for development in rural areas, do not typically make provision for papakāinga. Often papakāinga is seen as an inappropriate form of urban development in a rural setting. As a result; the ‘urban effects’ of papakāinga on the rural environment are closely examined by local councils.

Yet papakāinga is a traditional ancestral form of living that far outdates district plans. If developed to its traditional model of a small cluster development and with best practice design guides, papakāinga in my view is entirely appropriate for rural areas and is consistent with best practice design for rural areas. The type of development advocated by Randall G. Arendt’s “Conservation Design for Subdivisions”, which forms much of the basis of good practice rural design.

Going back some 10 years, I was very lucky to be part of a team at Taupō District Council who, on request from local iwi trust board Tūwharetoa Māori Trust Board; recommended to council a set of provisions that provided for papakāinga in the Taupō rural environment. The Taupō community agreed, by adopting these provisions into its District Plan. That was hugely satisfying and one of my career highlights.

Following on we didn’t see any papakāinga projects in rural Taupō for various reasons, mainly the cost of building. Then the Kiwi Bank and Housing NZ loan scheme – Kāinga Whenua; made funding for whānau more accessible, and along with the Te Puni Kōkiri guide to papakāinga, more are now starting to emerge.

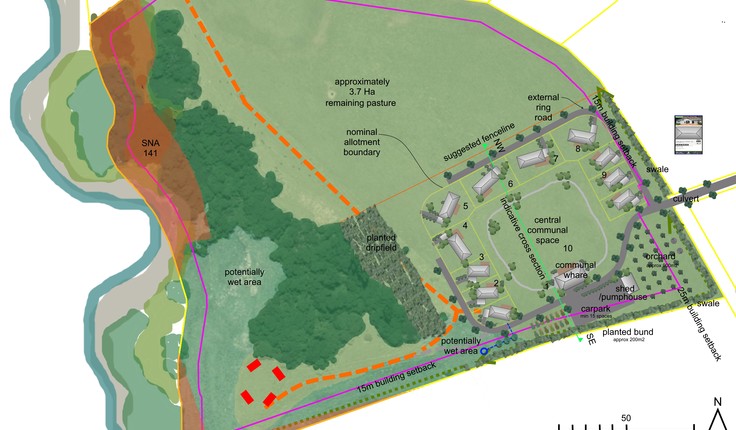

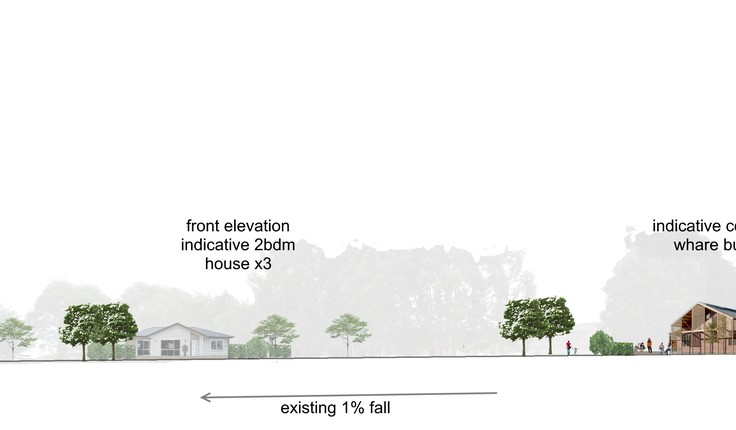

When I first got involved with our Tūrangi-based whānau’s papakāinga, I was invited by resource management practice Perception Planning, to produce concept plans to accompany their resource consent applications (while papakāinga is essentially permitted in the Taupō District Plan, there are still consents required for roading and infrastructure, and regional consents for water and wastewater). I later joined Perception Planning and prepared accompanying landscape and visual assessment.

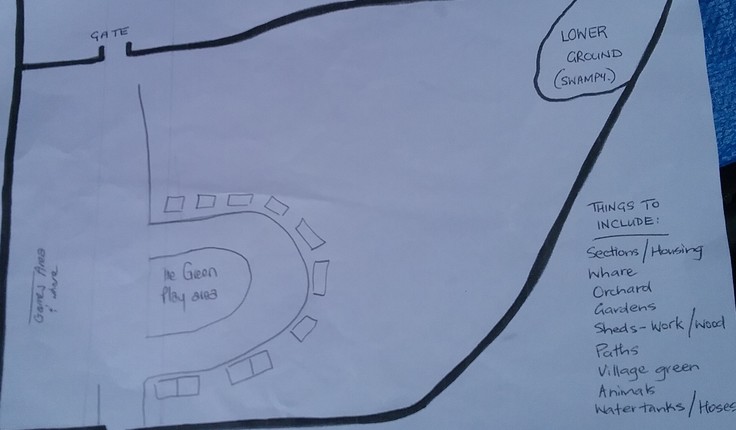

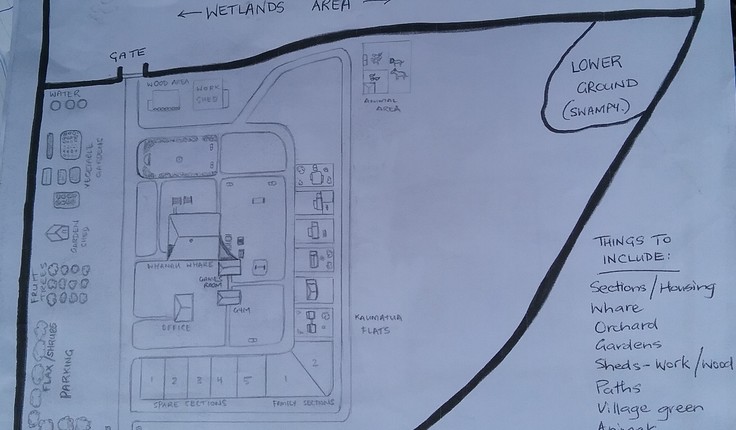

Our Tūrangi-based whānau had great visions and ideas and lead the concept process – I was just the drawing tool to put down their ideas and present in a concept plan. I felt incredibly lucky to help facilitate and guide their design process and be part of the journey to evolving their plans. A process that the whānau where so engaged with and passionate about, complete with bantering among whānau to see who would have the best sites or the best views.

The whānau wanted their papakāinga to be as sustainable and self-sufficient as possible. Their whenua is partly grazed, and partly remnant native riparian vegetation boarding a significant natural river corridor valued as a trout fishery. They wanted to protect and enhance their significant natural river environment, dedicate a place for rongoā, incorporate fishing huts and eco-tourism, and establish a strong community focus.

When I asked a member of our Tūrangi-based whānau why building a Papakāinga was important to her, she replied:

“The idea of living together and being able to be there for one another. To share the land and the fruits of the land. To pull resources and work towards cutting down on excess. To be able to create something that suits the lifestyle we want to achieve – self-sufficiency, unity and a good foundation for ourselves and others.”

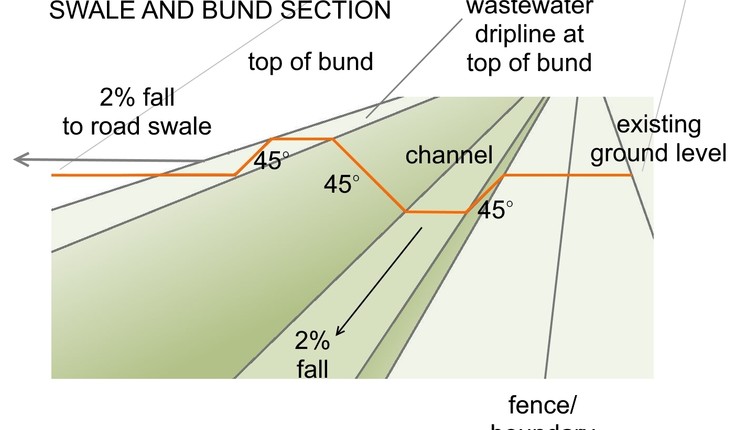

There are many factors to consider when developing a green field site. It requires a team of experts along with landscape architects including; stormwater, waste water, fresh water, engineering and planning. The goal to be sustainable and off-grid comes with many challenges, and this process from a landscape architecture perspective probably best deserves another article.

For now, our Tūrangi-based whānau have all their council consents granted and are currently at the infrastructure stage. The process, which started in 2015 is still ongoing, and has taken the whānau longer than they anticipated, but they are determined to keep going. When I asked what advice the whānau would pass on to others wanting to do the same, the answer was:

“Never give up, always keep working on it, if one door shuts look for another to open. Keep the dream and goals of why you want a papakāinga alive.”

And their vision for the future?

“That the papakāinga itself, the land and its surroundings and the people who live on it are happy, healthy and thriving”.

For me; papakāinga is a traditional form of ancestral living that fosters a more inclusive and caring community for whānau. I believe that papakāinga should be enabled in our planning and design guidance, so that traditional ancestral living is protected and encouraged. I have been lucky to experience the role that landscape architects have in facilitating, informing and shaping that planning and design thinking for papakāinga, and I believe it is important that we continue and collectively work together in this role.

Text and illustrations: Kara Scott (Te Whānau a Apanui): Kara is a member of Te Tau-a-Nuku-a-Nuku and a Registered Landscape Architect, she is based in Taupo where she runs her own practice

Share

12 Feb

NZILA lodges submission on Planning Bill and Natural Environment Bill

There’s still time to have your say

Tuia Pito Ora New Zealand Institute of Landscape Architects has lodged its formal submission on the Planning Bill and Natural …

09 Feb

Weekly international landscape, climate and urban design update

Monday 9 February

This is your weekly international snapshot of what’s happening across landscape architecture, climate adaptation and urban design. Drawing on credible …

02 Feb

RMA Reform submission update

Call for feedback and images

Submission framework The Environmental Legislation Working Group thanks all members who made the effort to join us at the national …

Events calendar

Full 2026 calendar